We often write about the opportunity for fixed income investors to lock in relatively attractive long-term rates. And we would argue that investment consultants and financial advisors have no more important charge than to convince their clients to take advantage of this while they still can.

Yet we are also well aware of the allure of the bird in the hand. The 12-month Treasury Bill (T-Bill) was yielding 5% as recently as July 10. Many banks were paying over 4% on demand deposits, and CD yields were higher still. Yes, these yields were attractive, but now they are already in the rearview mirror. We suspect that investors in T-Bills have already or will soon discover the perils of reinvestment risk.

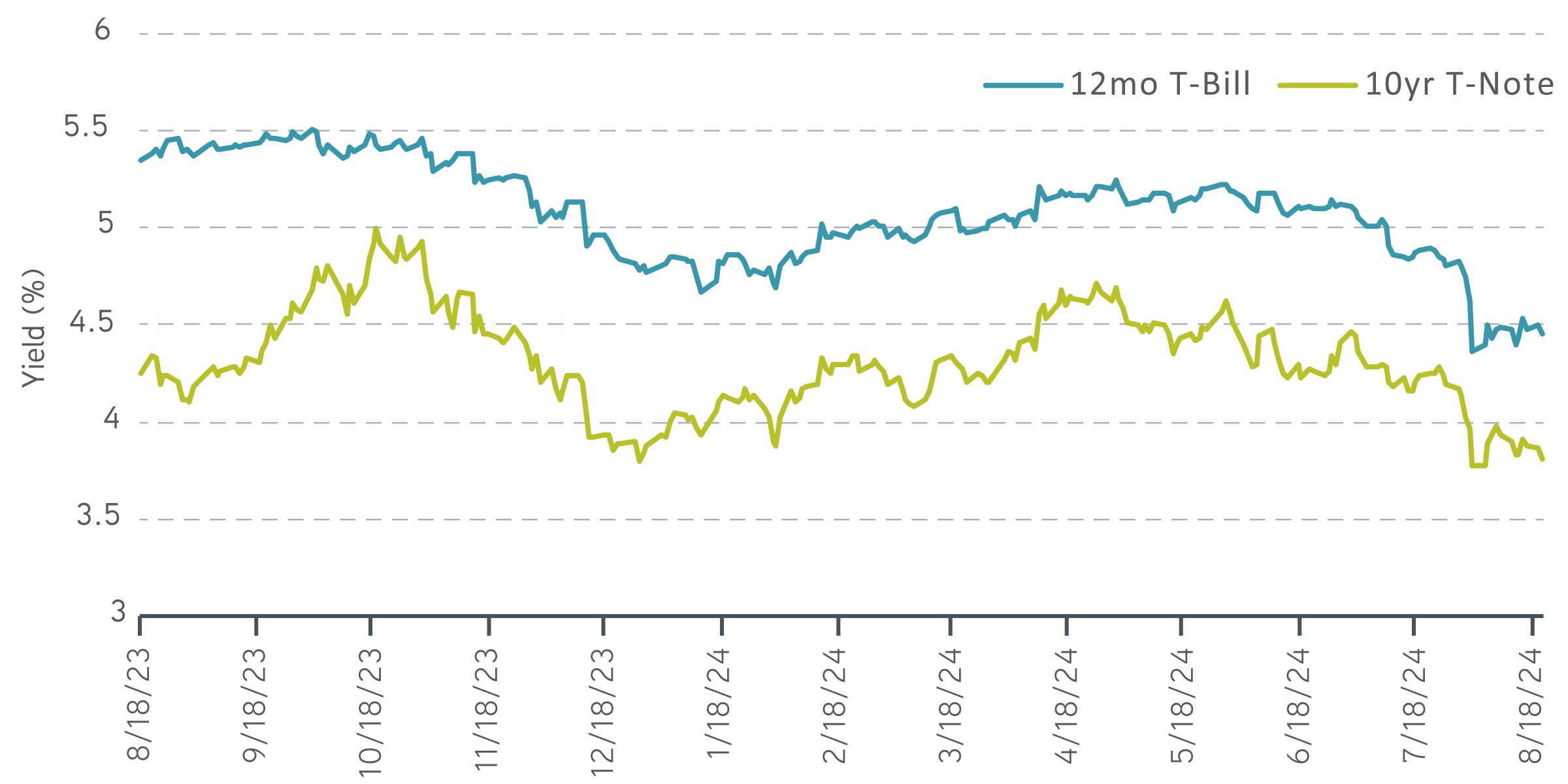

As of August 19, the yield on the 12-month T-Bill was down to 4.50%, compared to 5.34% the year before. The Fed has yet to act, and the rate has already declined 84 basis points (bps). Investors would be correct in pointing out that the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury Note (T-Note) has declined as well, but not in a parallel shift: To 3.87% from 4.26% a year ago, the benchmark yield’s decline of 39 bps is less than half that of the T-Bill.

Tracking yields: 12-month Treasury Bill versus 10-year Treasury Note

Source: Bloomberg, data from 8/18/2023 to 8/20/2024. For illustrative purposes. Not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investments are subject to risks, including the risk of loss.

Focusing on yield, buying cash flow

Investors often focus on yield, so many may still be prone to select the higher-yielding T-Bill—even though the differential with the T-Note has narrowed. What investors sometimes forget is that when it comes to fixed income, they are buying cash flow. Longer-term bonds simply offer more cash flow than short-term instruments. When rates decline, the value of cash flow usually increases.

A closer examination of the math from a year ago might help illustrate why this matters. We can compare the one-year after-tax total return, to an investor in the top tax bracket, on a $1 million investment in the 12-month T-Bill or the 10-year T-Note.

For our purposes, let’s assume that the 10-year T-Note is sold on the day that the T-Bill matures. Again, the T-Bill yield was 5.34% on August 18, 2023. The benchmark 10-Year T-Note on that date was the 3.875% due August 15, 2033 (CUSIP 91282CHT1), which was yielding 4.26% with a price of $96.9375.

After one year, the T-Bill would have paid $53,400 in interest, more than the T-Note’s $38,750 in coupon payments. But the T-Bill would mature at par, while the T-Note would experience price appreciation: The closing price on August 19, 2024 was $100.03125—a mark-to-market gain of $30,938. Combined with the $38,750 in interest, the 10-year T-Note would have generated $69,688 in total return.

Both the income and the capital gain are taxable as ordinary income.1 So the after-tax income for a top bracket payer would have been $31,613 (3.16%) on the T-Bill and $41,255 on the T-Note (4.12%). Despite yielding less, the 10-year T-Note would have produced an after tax-total return 96 bps higher than the 12-month T-Bill.

This illustration doesn’t take into account actual trading, management fees, transaction costs or other holdings and tax matters that could affect each investor’s experience. Nevertheless, we believe that today’s market conditions may have the potential to produce similar differences in outcomes.

Interest rate or reinvestment risk?

Some investors may be quick to point out that the T-Note’s higher return was likely a function of a risk differential. After all, the higher duration 10-year T-Note carries much more interest rate risk than a 12-month T-Bill.

But we would argue that the risk investors should be more concerned about today is reinvestment risk. Why? The Federal Reserve has told us that they are going to lower the federal funds rate. Historically, this has usually led to lower long-term rates. And lower long-term rates have tended to generate outperformance.

Solutions for today’s complex interest rate environment

The bottom line

Last year it clearly made sense to take on duration. We think it still makes sense to take on duration now to limit reinvestment risk later. Investors seduced by higher T-Bill yields—the bird in the hand—may likely miss out. Today we believe the bushes are filled with birds, tomorrow that opportunity may have flown.

1 For this analysis, we use the federal marginal tax rate of 40.8% for income and short-term capital gains, which includes the 3.8% net investment income tax.

Parametric and Morgan Stanley do not provide legal, tax or accounting advice or services. Clients should consult with their own tax or legal advisor prior to entering into any transaction or strategy.

The views expressed in these posts are those of the authors and are current only through the date stated. These views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions, and Parametric and its affiliates disclaim any responsibility to update such views. These views may not be relied upon as investment advice and, because investment decisions for Parametric are based on many factors, may not be relied upon as an indication of trading intent on behalf of any Parametric strategy. The discussion herein is general in nature and is provided for informational purposes only. There is no guarantee as to its accuracy or completeness. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments are subject to the risk of loss. Prospective investors should consult with a tax or legal advisor before making any investment decision. Please refer to the Disclosure page on our website for important information about investments and risks.

9.4.2025 | RO 3830947