With tax season upon us, many investors have received unwelcome surprises with their 1099-DIV forms—mutual fund capital gain distributions. Mutual fund companies generally issue estimates in the fourth quarter, yet some investors may be unaware that these distributions common to most funds can bring on additional tax burdens. While it’s too late to change the impact on prior year tax returns, now may be the right time to start thinking about strategies to reduce potential 2024 tax liabilities before filing next year.

Triggers of capital gain distributions

Capital gains occur when the mutual fund manager sells securities at a profit throughout the year, often after the value of an investment held in the fund has risen. By law, mutual funds are required each year to distribute capital gains proportionally to all shareholders as of a certain date, usually in mid-December. By contrast, mutual funds don’t distribute capital losses, which are instead carried forward to future years.

Investor redemptions or withdrawals throughout the year are another common reason for realizing and distributing capital gains. When investors sell shares, the value of those assets must be taken out of the mutual fund and delivered to sellers. If there is insufficient cash to meet redemptions, managers are forced to sell securities, which can trigger capital gains. Investors who stay in the fund end up paying taxes on capital gains accruing to assets that were redeemed from the fund.

Immediate impact on mutual fund shareholders

On the day that a mutual fund distributes capital gains, the value of the fund—known as the Net Asset Value (NAV)—is decreased by the same amount. No matter how long the investor has held the fund, the tax rate on that distribution is the same as the tax rate on long-term capital gains—that is, 0%, 15% or 20%, depending on their income level plus 3.8% for the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). Investors are obligated to pay these capital gains taxes whether they choose to pocket the cash or reinvest it back into the fund.

For example, if an investor held $100,000 in a mutual fund that distributed 10%, this would result in a $10,000 distribution, and a $2380 tax bill (at the maximum 20% tax rate plus the 3.8% NIIT).

Just because a mutual fund reports a capital gain distribution, that doesn’t mean the fund’s performance has matched or exceeded the stated benchmark. And investors who purchase a fund later in the year will pay taxes on distributed capital gains, even though they may not have benefited from the price appreciation leading to those gains.

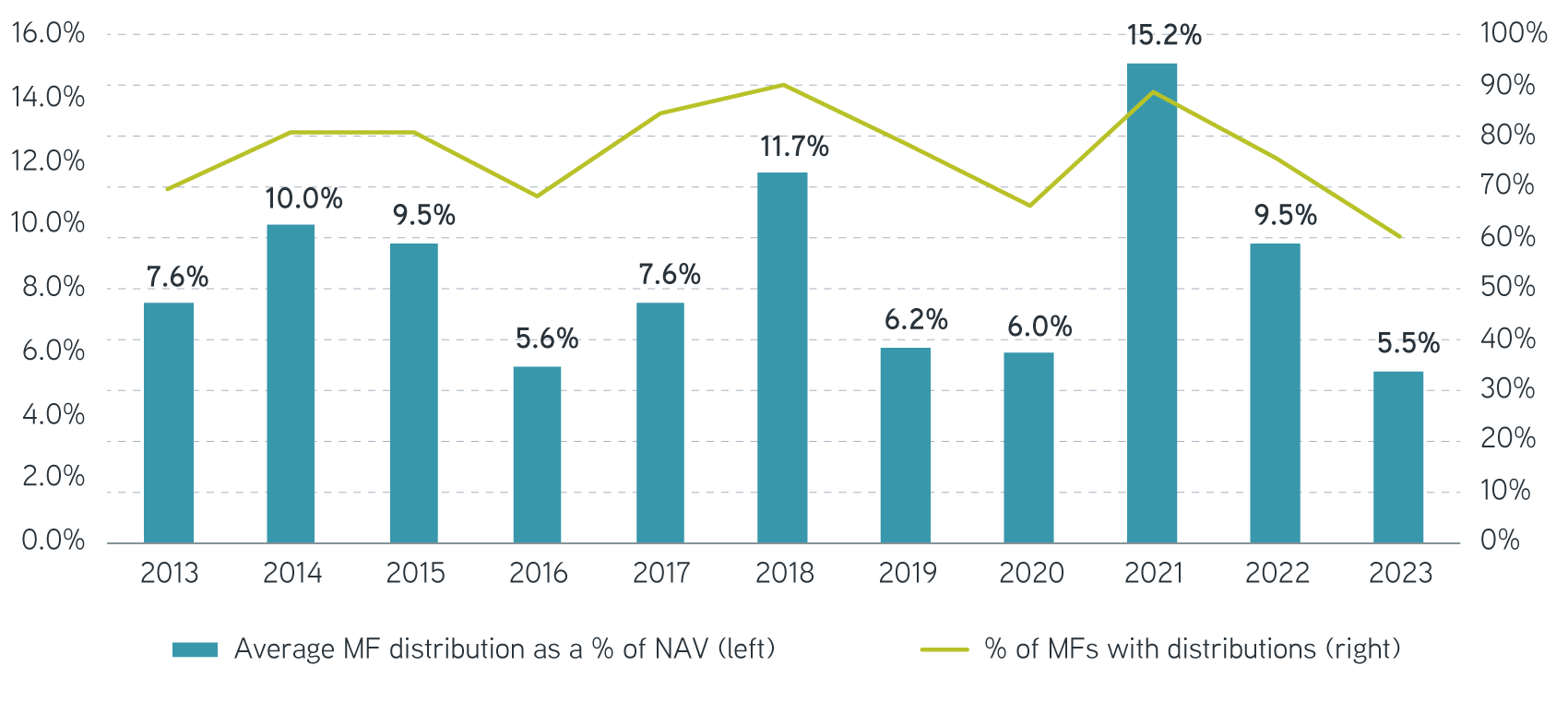

Typical mutual fund distributions

Over the past 11 years, capital gains distributions have been common, averaging more than 75% of mutual funds in Morningstar’s US Equity categories. The size of distributions has also been consistently high, ranging from 5.5% to 15.2% of NAV.

Mutual fund distributions over time

Source: Morningstar and Parametric. Morningstar US Equity categories. Includes mutual funds active during the reporting year. Data as of 2/28/2024.

In 2023, over 60% of US Equity mutual funds distributed capital gains, with an average distribution of 5.5% of their NAV. Notably, the top 10% of mutual funds distributed over 9.8% of their NAV. Even in challenging market environments like 2022, when the S&P 500® declined 17.9%, we saw 76% of mutual funds distributing gains, on par with the average. This could be attributed to higher investor withdrawals in 2022, with managers raising cash to meet those withdrawals by realizing accumulated gains after several years of high growth.

Longer-term impact through compounding

The tax cost of these distributions might be overlooked in any given year. Yet their full impact on investors can grow considerably over time due to their compounding effects.

Let’s consider the performance of two theoretical fund investments of $100,000. Each fund has the same performance, 10% annual growth. One fund distributes a capital gain of 8.7% each year, the average distribution over the last 10 years, which is reinvested. The other fund doesn’t distribute any gains.

After 20 years of appreciation, upon liquidation and after associated taxes, the investment that incurred annual taxes on capital gain distributions would have grown $89,000 less than the investment that didn’t distribute capital gains. In return terms, assuming the maximum 20% tax rate plus the 3.8% NIIT, the fund with distributions yielded an annualized after-tax return of 7.8% over 20 years, compared to 8.8% for the fund without distributions for the same period. The difference of one percentage point in performance can be described as the “tax drag” on the first investment.

Illustrative analysis of two investments

Source: Parametric research. For illustrative purposes only. Not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It does not reflect the experience of any investor and should not be relied on for investment decisions. All investments are subject to risks, including the risk of loss.

Mutual fund distributions force the realization of investment gains today, no matter how long the investor has held or plans to keep the mutual fund. The tax drag imposes an inherent cost on investors by eliminating the option to defer the gain until later. While taxes on those gains are inevitable, it can be strategically advantageous for investors to delay paying those taxes as long as possible. This is especially crucial for those planning to maintain long-term investments.

Plan tax management all year

How to limit tax costs of mutual fund distributions

One effective way to defer the tax impact of mutual fund distributions is to hold these funds in tax-deferred accounts like 401K plans or IRAs. Known as “asset location,” this approach delays the associated costs until withdrawal—essentially replicating a scenario in which capital gains aren’t distributed each year.

However, some investors may have maxed out their tax-deferred accounts, or they could be investing for a purpose other than retirement. Another approach involves using ETFs, whose distinctive structure allows the redemption of full baskets of securities when raising cash—thus reducing the frequency of capital gain distributions. On average, less than 8% of US Equity ETFs distributed capital gains over the past five years, with an average distribution of 3.7%.

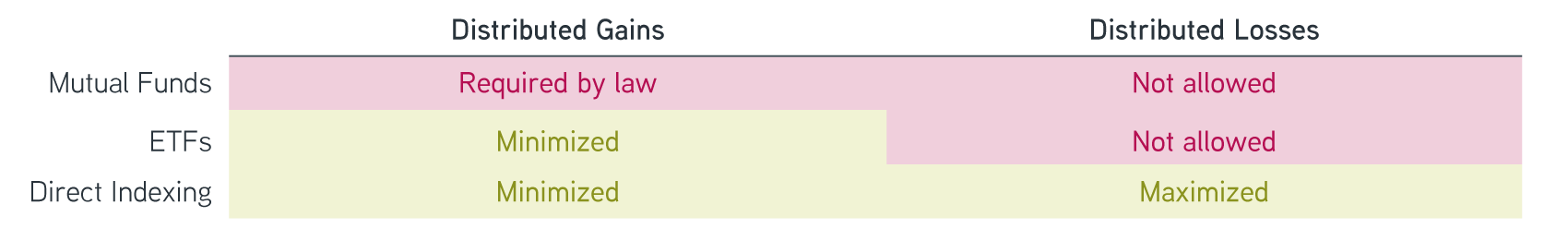

According to Morningstar, despite the meteoric rise of ETFs over the past two decades to about $3.3 trillion in the US Equity category, the mutual fund market remains larger, with over $4.5 trillion in assets as of February 26, 2024. While ETFs are less likely to distribute gains at year end, both ETFs and mutual funds share the same limitation that neither can distribute losses.

Direct indexing may offer a unique advantage over both mutual funds and ETFs. In these strategies, loss harvesting is a powerful tool used to offset annual capital gains. Loss harvesting involves regularly selling declining positions in the index to harvest realized losses, which can accrue to the investor in the portfolio.

These harvested losses can serve several purposes. Investors can use them strategically to offset capital gain distributions from mutual funds or any other capital gains they may have incurred throughout the year. Or they can defer them to offset gains in the future, which might include the eventual liquidation costs of their investments.

Comparing treatment of capital gain distributions

The bottom line

With tax liabilities for 2023 top of mind for investors, now could be a good time to evaluate the potential tax costs of capital gain distributions and formulate a plan to avoid, defer or mitigate them before the next tax season rolls around.

The proactive approach of direct indexing may allow investors to navigate the intricacies of capital gains more effectively, which could help to minimize tax costs in their overall portfolio. Depending on an investor’s tax situation, it may make sense to take advantage of direct indexing as a tool to increase tax efficiency, while simultaneously avoiding the tax drag from mutual fund distributions.

Parametric and Morgan Stanley do not provide legal, tax or accounting advice or services. Clients should consult with their own tax or legal advisor prior to entering into any transaction or strategy.